By our friend Michael Edwards from Liverpool

Liverpool has not been spared the impact of Covid-19. The city in the north west of England, home to roughly half a million people, is known amongst other things for its maritime history, popular music and football. Scousers are known as great talkers, great humourists, great socialisers. The city thrives on such inter-action and these days its economy is supported by a constant flow of visitors from elsewhere in the UK and from further afield. Following a lengthy period of economic decline, Liverpool’s reinvention over the past few years has seen it emerge as a popular tourist destination.

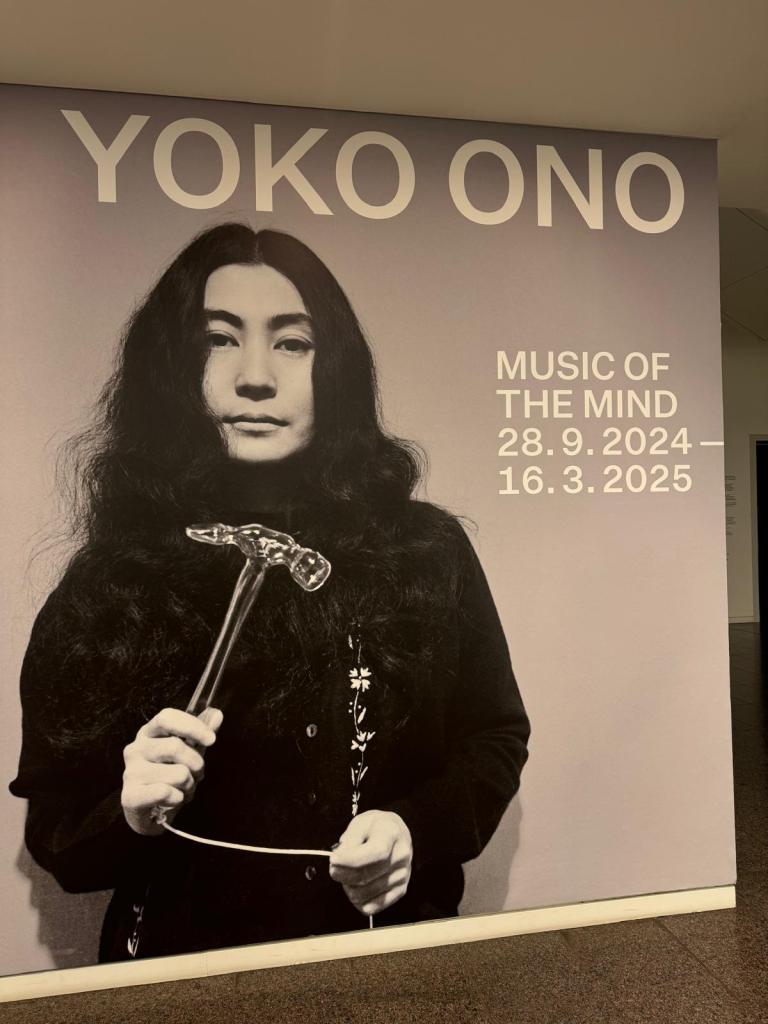

So the government restrictions imposed a little over a month ago, known collectively as ‘lock-down’, are difficult to digest. People are allowed to leave their homes for four reasons only: to buy essentials such as food or medicine; to exercise once a day; to work if home working is impossible; and for medical needs. Non-family gatherings of more than two people are banned. Pubs, bars and restaurants are closed, theatres and cinemas too, as well as most shops. Popular tourist attractions such as the Albert Dock [pictured], usually buzzing with visitors at this time of year, are almost empty.

And there is no football. For a city that lives and breathes the ‘beautiful game’, this would be painful in any circumstances. But when the English Premier League suspended matches, Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool FC were just two victories away from their first league title for thirty years. Hard to bear, unless you’re a supporter of Everton, the city’s other major club.

For the most part, people are coping. Many are now without work and relying on the government’s financial support. Others are adjusting to remote working from home. But some, especially those who make a hand-to-mouth living in the informal economy, are ‘slipping through the cracks’ left by the various support packages. Community-run food banks, hard-pressed at the best of times, have never been busier.

Before lock-down and in its early stages, panic buying stripped supermarket shelves bare of many commodities. Toilet roll and hand sanitizer were impossible to find for a time, likewise pasta and flour (who knew we had so many home bakers?). People have calmed down now and the supply chain has caught up with demand. Shops are now limiting in-store numbers, however, and supermarkets routinely have queues of people outside, each trolley kept at the required distance of two metres from the next.

Bereavements are particularly distressing in the current circumstances. Mourning has been disrupted by social distancing rules: funeral gatherings can involve only a bare minimum of family members, all keeping a safe distance from one another. Those that have lost loved-ones are deprived of the solace usually found in the comforting physical embrace of family or friend. Places of worship are also closed.

In Liverpool, as elsewhere in the country, the National Health Service is managing so far owing to the dedication of its workforce, some of whom are having to work despite a shortage of adequate protective equipment that has rapidly become a national scandal. The same issues affect care homes for the elderly, where cases are rising at an alarming rate. Liverpool’s Mayor has vowed to bypass the usual procurement process in order to obtain the protective equipment required. And people across the city are participating enthusiastically in a new national ritual: every Thursday at 8.00 pm, you can hear the sound of clapping as people congregate for a minute on their doorsteps to applaud the efforts and sacrifices of health care workers and others on the coronavirus front line.

People are helping each other. Liverpool City Council has started a volunteering scheme that – for the time being – has more recruits than are needed. Informal networks have sprung up in communities across the city. Whatsappgroups have emerged at street level with the intention of keeping people supported and in touch. Neighbours who have lived a few doors from each other for years without speaking are now sharing their daily experiences, from missing cats to family tragedies.

And the city’s roads are different. There is a fraction of the usual volume of traffic. Conversely, more people can be seen out making the most of their daily ration of walking or running, some perhaps appreciating the value of exercise for the first time.

At the time of writing, Liverpool remains in the grip of the pandemic and the measures to stem its advance. Confirmed cases in the city have been rising sharply in April and passed one thousand around the middle of the month. But testing is still selective and the real number of cases must be far higher.

The current restrictions will remain in place at least for the next three weeks and possibly much longer. The people of Liverpool are yearning for their former lives. In the words of the Liverpool FC anthem, “At the end of a storm, there’s a golden sky and the sweet silver song of the lark.” For now, the end of the storm seems some distance away.